Pont du Gard - Ancient Roman Bridge

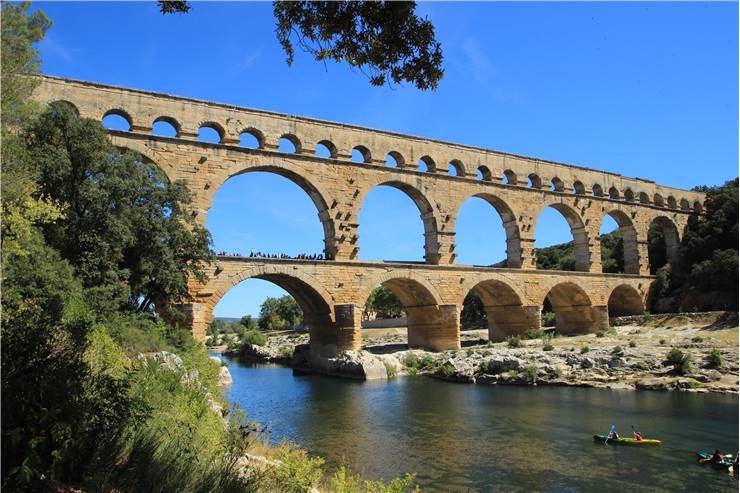

Pont du Gard is an impressive ancient Roman aqueduct that served as the main component of the 50km-long canal that carried water between the spring at Uzès to the Roman colony of Nemausus (Nîmes). Created 2000 years ago in the 1st century AD, this aqueduct to this day remains the highest elevated Roman aqueduct of all time, and together with Aqueduct of Segovia one that was best preserved.

Built over the period of just around 15 years in 50AD using 30 million shelly limestones, Pont du Gard aqueduct has the form of three arched bridges placed one atop of other. The top of the bridge features water-carrying channel with a constant gradient of just 2.5cm from one side of the bridge to another. The Roman architects had access to very impressive construction techniques, which enabled them not only to create this 50-kilometer Nîmes aqueduct network in short period but also to have it loose only 17 meters in height over its entire structure that passes via underground passages and through numerous mountains. The overall gradient of the entire Nîmes aqueduct network is just 1 in 18,241, which is much lower than many other Roman aqueducts.

Pont du Gard today stands 48 meters (160 feet) tall and 275-meter-long, but in its original state, it was much longer at 360 meters (1,180 feet). Its three-tiered arched design was revolutionary for its time, managing to span Gardon river below it with a central arch that is 24.5m wide, a record for any structure that was built in 1st century AD. The entire construction featured 64 spans (6 in the lowest section, 11 in mid and 47 in highest), although the top section is today missing 12 of the arches.

Pont du Gard bridge is the most important showpiece structure of the 50km-long Nîmes aqueduct network that was created in 50 AD

The aqueduct was in use between 1st to 4th century AD, with some part of the network remaining operational even to the 6th century. By that point entire structure fell into disuse, and natural clogging and lack of maintenance caused a buildup of natural material that blocked the flow of water. Instead of falling to ruin like the majority of the original Nîmes aqueduct network, Pont du Gard managed to survive due to its ability to be used as a pedestrian bridge. Local lords and bishops were required to preserve the bridge in the operational state, collecting tolls and keeping this structure in the good state.

By 17th century bridge was still operational, but some of its stones were damaged, missing or were looted. By the 18th century, this historic aqueduct started gaining more and more attention from both the local governments and the international community, and it eventually became a popular tourist landmark. After the 18th century, several organized efforts by the French state and local authorities led to restoration and preservation of the Pont du Gard bridge structure. In 2000, Pont du Gard was finally fully transferred into a site of historic heritage, transferring pedestrian traffic from it and into a nearby visitor’s center. The aqueduct and the scenic area immediately surrounding Pont du Gard are protected by French “Monument Historique” (1840), French law (1930) and as UNESCO World Heritage Site (1985), where it was described as a mark of masterpiece of human creation, in the same way as Taj Mahal and Great Wall of China.

Today, Pont du Gard is one of the most popular tourist attractions in entire southern France.

History Pont du Gard

Origins

The origins of the Pont du Gard aqueduct can be traced all the way back to the early years of 1st century AD, when Roman emperor Augustus' son-in-law and aide, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, was tasked with managing water supply for Rome, Italy and all of its numerous colonies. In the position of the senior magistrate (aedile), Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa formed plans, gathered funding and organized work for the creation of several large aqueduct networks, with Nîmes network being the largest and longest lasting. While the old common consensus was that the work on the Nîmes aqueduct network started around 19 BC, newer findings have confirmed that the majority of the tunnels that were used to transfer the water from spring at Uzès to the Roman colony of Nemausus (Nîmes) were built between 40 and 60 AD. This was confirmed by several findings of worker coins that started circulation no earlier than the reign of Roman emperor Claudius (41–54 AD). Modern historians argue that the entire construction of the Nîmes aqueduct network was set between 40 and 60 AD, has lasted around 15 years, and it used workforce that numbered between 800 and 1000 workers. Stones for the creation of Pont du Gard aqueduct bridge were sourced from the quarry that was located only 700 meters from the bridge itself.

After Roman Empire

Nîmes aqueduct network remained in regular use between 1st and 4th century AD, but the fall of Roman empire and arrival of several waves of invaders managed to disrupt the region and almost totally remove the maintenance efforts that kept the water tunnels free from clogging and being structurally safe. With each passing decade after that, parts of aqueduct network started being compromised, eventually leaving only parts of the waterways in active use in 6th century AD. By that point, Nîmes aqueduct network stopped being operational over its large part, clogged with encrustations, plant rot, debris and losing water via destabilized construction. Some evidence, however, suggests that pieces of the network continued to be used for water transport even up to the 9th century.

While the natural decay and looting compromised Nîmes aqueduct network, French authorities and local governors managed to preserve the Pont du Gard aqueduct bridge because it was actively tolled as the only fast and reliable way to traverse the Gardon river valley, and those funds were used for its maintenance.

Another factor that contributed to the lack of additional damage to the bridge was the fact that it was not located in the highly populated area of France. Builders of Pont du Gard placed it on the location that best-suited transport of water, and not near any major roads or settlements. This reduced the amount of foot and cargo traffic in the area, enabling the bridge to avoid the high stress of constant public use.

Even with that, for centuries Pont du Gard remained the only safe passage point over that part of Gardon River, and slowly and surely, pieces of it started falling off, being looted or removed away (most notably by local monks who used its stonework for construction).

Damage in the 1600s

The rights of the maintaining the bridge were given by French king to seigneurs of Uzès, and later to Bishops of Uzès. They tolled the bridge and were responsible for its maintenance.

Pont du Gard stood in good health for over 16 centuries, but that era came to an end during the 1620s war between French Royalists and Huguenots. When Henri, Duke of Rohan and leader of the Huguenots elected to use this bridge for transporting a large part of his artillery, he ordered the partial destruction of the structure of the bridge. Because there was no space for artillery to be carried across the bridge on its lowest deck, Duke ordered cutting off a third of the thickness of the one side of the second row of arches. This alteration enabled passage of artillery, but it also dramatically reduced the carrying capacity of the entire bridge. In the years following this alteration, the lowest level of Pont du Gard bridge become passable for larger carts, but the compromised stability of the bridge started worrying architects and surveyors, who feared that bridge could potentially fall if any of its remaining core structural parts become damaged.

Henri Pitot’s Bridge

One of the possible solutions for preservation of the Pont du Gard aqueduct bridge arose in early years of 18th century. The local authorities commissioned the restoration of the bridge that would reinforce the damaged arcs, strengthen the piers that were badly damaged, replace the missing stones, and repair various parts of all levels of the bridge. The most notable addition was the 1743-1747 construction of the new bridge that was located just next to the arches of the lowest level of the bridge. Devised and realized into reality by architect and engineer Henri Plot This new side-bridge was intended to be used by foot and cart traffic, displacing much of the weight by passengers and cargo from Pont du Gard to this new bridge.

While this side-bridge reduced the strain from Pont du Gard, many of the locals and numerous worldwide authors criticized the move, citing that this new structure has ruined the look of the original bridge and the scenic environment around it. The most vocal and notable critic of Henri Pitot’s bridge was famous French novelist Alexandre Dumas who commented that “it was reserved for the eighteenth century to dishonor a monument which the barbarians of the fifth had not dared to destroy."

However, even with the moving of the traffic to the side bridge, the Pont du Gard continued to deteriorate. Its damaged arches, loss of stonework and slow erosion slowly but surely made the bridge more and more unsafe, leading surveyors of early 1800s to believe that the collapse of the bridge was imminent.

Renovations of Napoleon III

Considerable attention fell on the Pont du Gard bridge after Napoleon III, nephew of the first Napoleon, visited this site in 1850. Seeing the bad shape of the bridge, he felt compelled to commission large restoration project funded by Ministry of State that would restore the aqueduct bridge to its former glory. The project was led by the architect Charles Laisné who oversaw the restoration process between 1855 and 1853. This included filling of piers with concrete to make them more durable, improving drainage, replacing many eroded or missing stones, and separating the water channel of the bridge from the rest of the aqueduct network (thus protecting it from further water damage). The top of the bridge and the water conduit were restored, enabling visitors to climb up via newly installed stairs all the way to the aqueduct and observe it in relative safety.

All this made the Pont du Gard bridge even more appealing to tourists, who started visiting this area of France with increased frequency. Pont du Gard was also declared to be a “Monument Historique” by the French government in 1840.

Modern History

In recent history, Pont du Gard managed to survive several floods (even the massive 1958 flood that submerged entire first level of the bridge underwater) and was subjected to several restoration projects that consolidated its piers and arches.

Today, the area of the bridge is protected by the government, and tourist can engage numerous activities both on and near the bridge. This includes a local museum focused on the history of the bridge, child area, cinema, open air route, temporary exhibition, history trails through nature and other events.

In 2004, Pont du Gard was the first historical object that received the label of “Grand Site de France” by the Ministry of Ecology and Sustainable Development.

Architectural details (Description of the bridge)

Pont du Gard was built over the valley of Gardon river in southern France. Its original construction was augmented with a side-bridge structure that dramatically widens its base level, placing a decking that could be used by both on-foot and cart traffic. Today, two millennia after it was originally constructed by builders of Ancient Rome, Pont du Gard still stands 49 meters tall above the level of the river, and 247 meters across the Gardon valley. The width of the bridge was originally smaller, but the 18th-century side-bridge expanded it to 9 meters. On the top, the aqueduct bridge remains 3m wide, with each of the rising levels of the bridge receding above the main piers.

The entire bridge structure is estimated to be weighing around 50,400 tons of limestone, mortar, and clamps. The volume of the bridge could fit inside 21,000 cubic meters, and some of the heaviest blocks of stone are estimated to be weighing around 6 tons. All the stone that was used for constriction of this bridge was excavated from the nearby quarry that is located just 700m in the downstream direction. All the stones were precisely cut to perfectly fit one with another , which enabled builders not even to use mortar. The mere friction between perfectly cut and aligned pieces of heavy stone provided enough binding power to keep entire bridge stick together.

Because of its lack of use of mortar, the Ancient Roman designers rarely used this kind of approach to creating large aqueducts or structures since it required very large amounts of stone to be cut and precisely placed. Later aqueduct structures used much less stonework that was held together with binding properties of very effective mortar. This enabled them to create larger, taller and more slender arches that could be placed on less reinforced piers.

Pont du Gard features three distinct bridge levels, all with their number of arches that are constructed independently one from another to provide better structural support and flexibility. The number of arches, the thickness of piers and height of arches differs for each level, and is as following:

- Base level – 6 arches that go up to 22m in height, piers are 6m thick.

- Middle level – 11 arches that to up to 20m in height, piers are 4m thick.

- Upper level – 35 arches (originally 47) that go up to 7m in height, piers are 3m thick.

The top of the upper level of the bridge houses a water conduit (specus) that is 1.2m wide and 1.8m high. While the rest of the bridge features crude stones that were not decorated, the specus conduit itself was precisely cut and polished to perfection. The walls of the conduit itself were made out of masonry, and the floor was done from concrete, and the entire structure was covered with a stucco made from small shards of pottery and tile, painted over, and covered with a maltha texture. This process ensured that the water conduit remained smooth, durable and perfectly safe for long-term water exposure.

Because the purpose of the entire bridge is to passively transport water via slight difference of gradient, only the specus section bridge has the needed drop of height that facilitates the flow of water. This is achieved by mere 2.5 cm difference in the height of specus between two sides of the bridge. The rest of the bridge is almost perfectly leveled and structurally sound, with the slight lean being present in the upstream direction of river Gardon. Initially, this was believed it was done to better protect the aqueduct bridge against floods, but recent findings discovered that this bend was a result of the heat expansion of one set of stones that caused entire bridge to permanently sway in an upstream direction a little.

Created without the use of mortar, Pont du Gard helped deliver 200,000 cubic meters of water each day

The Nîmes aqueduct and Pont du Gard

Large and wealthy colony Roman city of Nemausus (Nîmes) that housed 50 thousand inhabitants faced a water issue from its inception. The engineering effort to bring water to it required aqueduct builders to turn their sights on the northern mountainous region that featured several springs, as the other directions around the city were unsuitable (either due to lack of sources of water, or because of low plains that could not facilitate natural flow of water toward the city).

The chosen source of water for the city was springs of the Fontaine d'Eure near Uzès, which were located 20km from the city via air route. The aqueduct structure itself had to snake over the much longer route, circumventing large foothills of the Massif Central and taking around 50km of the passageway to reach the city finally. The area in question was harsh and filled with natural obstacles such as hills, gorges, dense vegetations and deep valleys. Roman architects frequently chose not to drill single large tunnels through mountains (in this case they would need up to 10km of almost straight tunnel to circumvent harsh terrain), so they picked a rough V-shaped route for their aqueduct structure that would start at 76m above sea level and then gradually slope down only 17m during the entire 50km passage to the city. In the end, much of the aqueduct ended up being placed inside tunnels, in fact, the aqueduct is underground in 35 of the total 50km of the entire structure. The aqueduct's gradient varies depending on terrain, but it averages to 1 in 3,000, which is much lower than many other aqueducts that were built by Romans (famed aqueducts in Rome had ten times larger gradient). On the Pont du Gard bridge itself, the gradient is 1 in 18,241 (2.5cm drop in 456 meters).

Tourism

Pont du Gard aqueduct bridge was famed for its beauty since the moment it was created. The high appeal made it one of the premier tourist destination in France, including a spot on the famed traditional tour around the country “Compagnons du Tour de France” that many Frenchmen strived to achieve during their lifetimes. The popularity of the bridge skyrocketed in the 18th century after a side-bridge was constructed to it, enabling tourist to personally traverse across the bridge. French government reacted quickly to rise in tourist activity, making Pont du Gard and the surrounding scenic environment protected as a cultural site.

Over the history of France, many of their monarchs strived to associate themselves closer with surviving symbols of strong Roman imperial power, which included both collectible antiquities and preservation of famous structures. This includes visits of Charles IX of France in 1564, Louis XIV in 1660, and Louis XVI who commissioned various pictures of Pont du Gard that were placed in his new dining room at the Palace of Fontainebleau. Patronage of Louis XVI was also essential in gathering funds for the 1850s bridge restoration which enabled Pont du Gard to survive to this day.

Tourists and regular travelers could visit and pass over Pont du Gard side-bridge all the way up to 1990s. The ever-increasing foot and vehicle traffic congestion over 1743 road bridge brought numerous problems to the preservation of the bridge. This also included the ever-increasing occurrence of building illegal structures near the bridge (mostly tourist shop). This all ended in 1996 when General Council of the Gard and French Government executed a plan to clear the surrounding area around the bridge, and restore it to the previous natural glory. The redevelopment included the closing of the bridge to the general traffic and building of the nearby museum that provided much additional information and historical context for this large structure.

Today, two millennia after it was originally created, Pont du Gard is one of France’s top five tourist destinations, with more than 1 million people visiting it every year.